Home Main Reference Page Main Index

Josephine Hartwell Shaw / House Beautiful -- House Beautiful magazine did two stories on Josephine Hartwell Shaw in 1915. The first covered her jewelry making. The second highlighted her home in Duxbury, Massachusetts, called "Three Acres." Shaw (1865 -1941) was one of the most important Arts & Crafts jewelers. In addition to creating distinctive and elegant objects, she was a mentor for Edward Oakes, who apprenticed with her.

From Kaplan's The Art that is Life: "Josephine Hartwell Shaw's jewelry attracted considerable awards and patronage. Following training in the late 1890s at Massachusetts Normal Art School and Pratt Institute, Mrs. Shaw taught drawing courses in Providence and near Philadelphia. She began her handicraft career as a metalworker and in 1905 was elected a Craftsman member of the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts. Her jewelry came to public notice in 1906 (about the time she married Frederick A. Shaw, a silversmith and sculptor), appearing in Good Housekeeping magazine and the historic decennial exhibition of the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts. The Boston Museum of Fine Arts exhibition of the Society's selections in 1913 included a brooch and ring that was purchased by the Museum for its collections, an unusual instance of contemporary handicrafts being acquired by a major art museum; a year later Mrs. Shaw was among the early recipients of the Society's Medalist award... Mrs. Shaw was widowed by 1914, when she left Boston for nearby Duxbury; there her neighbor, Atherton Loring, a life member of the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts, purchased this superbly crafted necklace or his wife."

"Mrs. Shaw featured sensuous color combinations in her jewelry and, in the manner of Arts and Crafts jewelers, probably considered their suitability for each client. [A Shaw necklace in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston] which...is worked both front and back reveals Mrs. Shaw's great technical skill and extraordinary sense for composing color, form, and texture, which she also passed on to her apprentice, the well-known Arts and Crafts jeweler, Edward E. Oakes."

Kaplan says that "beginning in 1908 Shaw exhibited eleven times at the Art Institute of Chicago's arts and crafts annuals, where her jewelry received highest awards in 1911 and 1918." However, Meyer, in Inspiring Reform, states that "Shaw exhibited in Boston's tenth anniversary exhibition in 1907, and beginning in 1908 was a regular exhibitor in Chicago, winning medals in 1912 and 1918."

According to Meyer, Shaw studied with Arthur Wesley Dow, and was a teacher herself at the William Penn Charter School, Philadelphia, and later in Providence. And "in 1901 and 1902 Shaw attended Harvard's summer school in the theory of design under Denman Ross and Henry Hunt Clark."

Meyer adds: "...Shaw took on Edward Everett Oakes as an apprentice. Later she would refer customers to him for jewelry repairs. Also in 1914, two years after her husband's death, Shaw moved from Brookline to Duxbury. In the 1920S she maintained a well-known tearoom in her historic house during the summer, making jewelry during the winter. She made jewelry for Julia Marlow Southern, a prominent actress and Arts and Crafts patron, as well as for members of Boston's elite. Hard hit by the depression, Shaw resigned from the Society in 1939."

See also chicagosilver.com/keystone.htm and chicagosilver.com/good_house.htm and chicagosilver.com/rogers_hale_mag.htm

|

|

|

SOME JEWELS AND A LANDSCAPE BY RALPH BERGENGREN

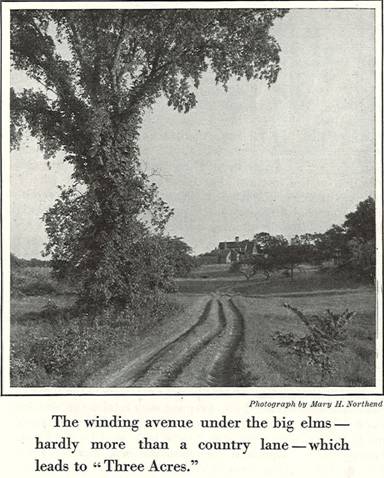

A ROOSTER crowed: evidently there was human life somewhere in the neighborhood. But no house in sight looked inhabited, and the invisible hero rested content at having imparted, with a single vocal effort, a Sunday morning feeling to a midwinter afternoon landscape. Closed apparently for the winter, the few scattered dwellings stood aloof among tawny, frozen fields; and the road, corrugated with frozen ruts and distantly crossing the railway track along which I had hopped from tie to tie in a short cut from the Duxbury station, appeared only to lead from one mysterious wood to another. Seemingly it was the last place in the world to look for a jeweler. I went back to the crossing, where the crossing tender, dimly visible through the frosted window of his little house, sat hugging the stove and gathering his forces to rush out, an hour or two hence, and warn the public that a train was coming. I knocked on the door, shivered in the wind-blown sunshine, and asked to be directed to the Duxbury Shop. Optimists at the station had told me I would see it as soon as I got to the crossing, but had neglected to add that it turns its back on the road and looks in winter like a shut-up studio. The crossing tender opened his door as little as possible and pointed it out to me.

To explain this search for a jeweler jewel-maker is a better term, in that it says good-by to the jewelers and jewelry with which we are all more familiar it is necessary to go back and start over again in Boston.

Some years ago a certain distinguished woman, attracted by the unusual and distinguished setting of a certain ring, bought it in the salesroom of the Boston Arts and Crafts Society, put it on her finger, wore it to New York and eventually into the gallery of a New York art dealer. The dealer noticed it, asked permission to examine it more closely, looked at it this way and that, and expressed an opinion.

"Ah!" said he, "this is one of the old Italian masters." And he offered, deferentially but unsuccessfully, to buy it for about five times the price that the wearer had paid for it. |

|

|

|

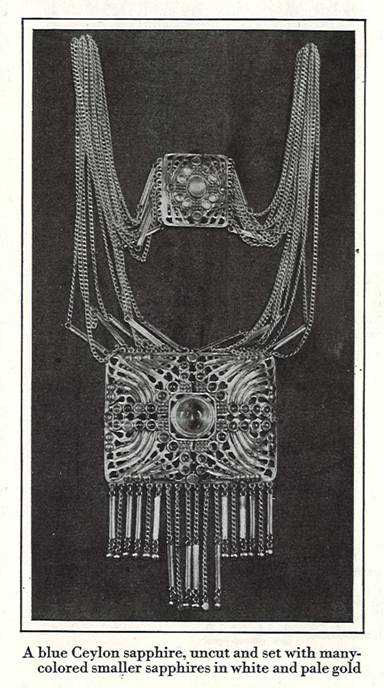

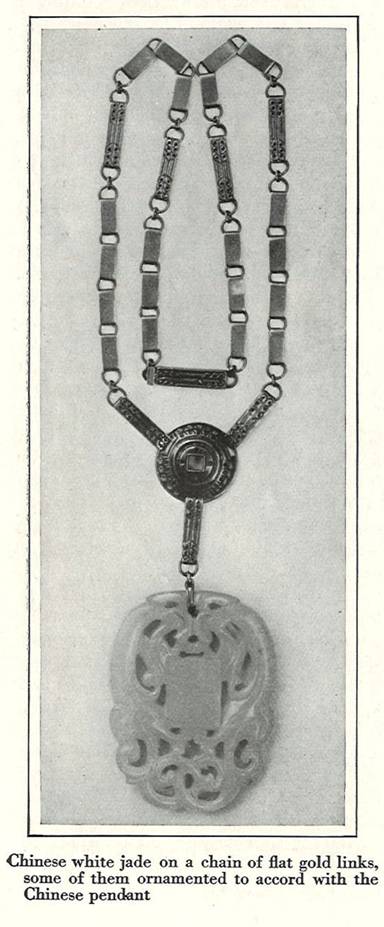

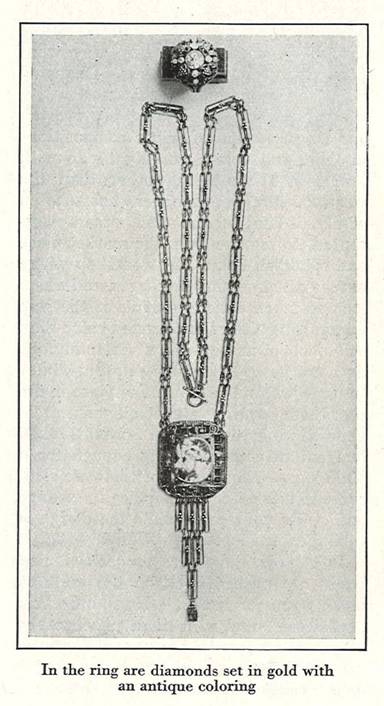

This ring had been made by Mrs. Josephine Hartwell Shaw, then working in Boston. The wife of a sculptor, Mrs. Shaw had been first a teacher of art and then a goldsmith and jewel-maker, because she saw in gems the possibility of combining and setting them, not only for-their intrinsic value as precious minerals, but for their essential beauty as crystallized color. It was as if one had little fragments of the sunset, bits of landscape, or-drops of the ocean, solidified in this or-that chromatic variation, to be combined into jewels that should. have a charm akin to that of nature as it is seen and perpetuated by the painter. Unity, in short, is the same quality whether it describes the work of a Sargent, a Whistler, or a Benvenuto Cellini. And in the fabrication of such jewels each detail must be of equal importance: the color of the metal must harmonize with that of the gems; the decoration of the metal must produce a design by which the gems are not merely exhibited but of which they are actually an important detail. Mrs. Shaw, for example, sometimes sets diamonds in silver rather than gold because the silver harmonizes with the diamond; and as for gold itself, she works in several colors of the precious metal, and has her own method for producing variations of tone as a given setting requires them. Such a conception of jewel-making takes its place immediately in the scheme of individual craftsmanship that has made the Arts and. Crafts movement another "renaissance" after the "dark ages" in which for a while machinery so widely eliminated individuality from the decorative side of life. It was a point of view that opposed the "blaze of diamonds," within quite recent memory an obvious ideal of jewelry, by making the value of a jewel depend as much upon the design and workmanship (which, after all, is as rare as a diamond and much more admirable) as upon the material. One is reminded of Ruskin's saying that the person who wears a cut gem for the sake of its value is a slave-driver, because the cutting of the precious stones requires little exertion of any mental faculty; but that the "designing of grouped jewelry may become the object of the most noble human intelligence," and then the cutting of the gems becomes perfectly allowable.

So Mrs. Shaw became a jewel-maker, working with the precious as well as the semi-precious gems, and adding out of her own craft the quality of distinction that makes the result valuable to those with eyes to see it. It is hardly surprising that such eyes were few enough in the beginning; but the Arts and Crafts Shop in Boston was already a little island of original work in the ocean of machine-made products, and there Mrs. Shaw's jewels began to find their public. For in jewelry, as in other forms of competition between the craftsman and the factory, the factory at its best can turn out a product that may well puzzle the discrimination of purchasers. I bow my head to the wrath of those who disagree with me. One must compare the work of the skilled craftsman, not once but many times, with the best that the factory can do in competition before one sees and then the discovery is final that humanity is superior to its own inventions; and that a craftsman is alive and a machine isn't. For example: here is a machine-made brooch on the jewel-maker's work-table, which has been sent her in order that she may make earrings to "go with it" and here is one of the earrings. I am not ashamed of admiring the brooch, which is a pleasant thing to look at; and I am puzzled to state, in a plain, understandable way, just why the earring is pleasanter. You must take my word for it. |

|

|

|

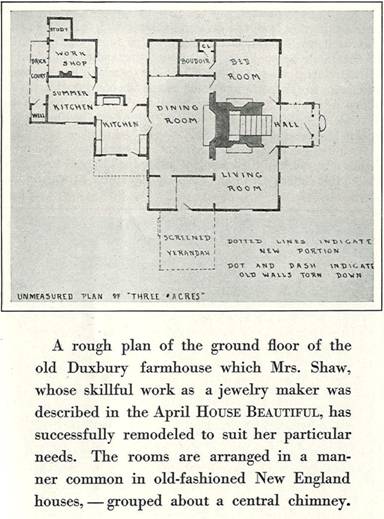

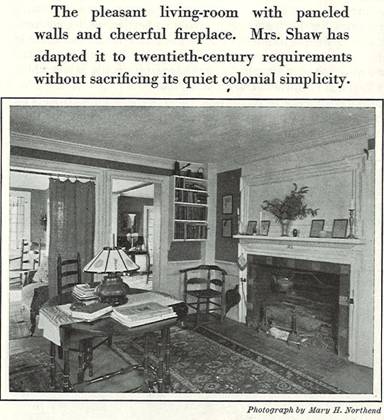

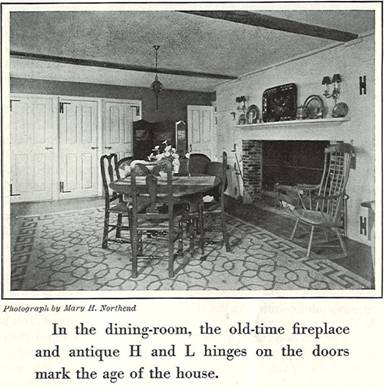

Mrs. Shaw lives in an old colonial house, comfortably modernized; and with her lives Miss Elizabeth Leete, who in summer dispenses antiques and tea at that very Duxbury Shop so plainly visible from the railway crossing; and with them an Airedale terrier, of a hearty, sociable nature, and a matronly tiger (or tigress) cat who seems to regard him as rather a vulgar fellow. The house turns its back on the road, looking out, instead, over a little pond that nature has set in trees and shrubbery, doing in its own way what Mrs. Shaw does with gems. Changing with the seasons, and for that matter with every hour, the little pond provides an endless succession of subtle compositions in light and color. Having to do with jewels in the making rather than the wearing, the jewel-maker has chosen wisely, when success and orders warranted, to remove from the market place and establish home and workshop where nature still grows her own trees, and where it is so much easier to think of the gem minerals as bits of imprisoned color than as objects of money value. Certainly one does not go to the country in mid-winter to wear jewels, but it is a fine place to design them, wearing a neat gingham dress yourself while you are at it. And this table, in front of a fireplace big enough for a Yule log the actual workshop we shall come to later is a fine place to arrange and study your gems while the design is taking expression.

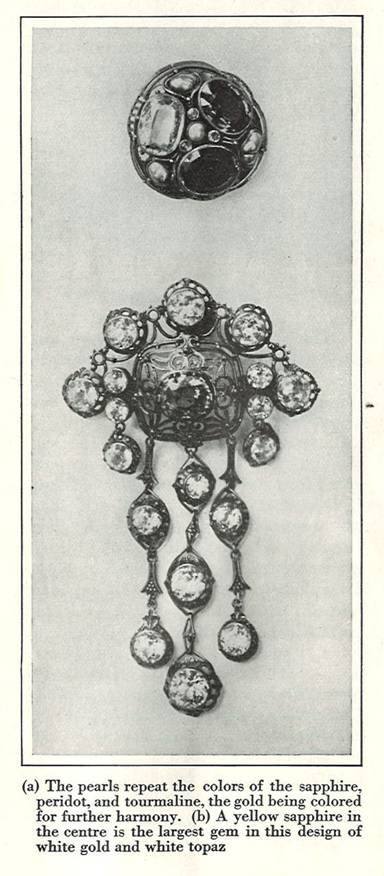

Just now, however, magazines and books are pushed back on the table to make room for jewels, rings, brooches, necklaces, and with them photographs of yet other jewels, the names of whose present owners would make my modest article take on the semblance of a Society Column. And I am not going to attempt describing them. The art of the jeweler lacks a vocabulary, of criticism such as serves somewhat to translate a painting or even a symphony into the terms of another medium. To say that a certain brooch sets a blue-green tourmaline, a blue sapphire, and a yellow peridot in greenish gold and pearls gives no real impression of the jewel. But if we go about it judiciously, concealing under the guise of general conversation our ultimate purpose of finding out what the jewel means to the maker, we will discover that here in miniature is the little ice-fringed pond reproduced in terms of sapphire, tourmaline, and peridot; and that the jewel-maker, selecting and arranging her gems and greenish gold, has sought to record the feeling that sometimes comes to her when she looks out of the window. But this is a secret. Mrs. Shaw is a practical-seeming woman and knows by experience that a great many people cannot see any relation whatever between blues and greens and yellows in a pond and blues and greens and yellows in a jewel. She tells of the lady with the lorgnette whom she once saw looking at some of her jewelry on exhibition. And when she had looked for fully thirty minutes, the lady sighed audibly. " I have been told," said she, "that this jewelry is unlike other jewelry. But I don't see any difference." One may suspect, however, that this lady was looking at the gems rather than the settings from the point of view of the jewel-maker she should have been looking at neither separately, but at both together and that her critical opinion was based upon a conviction that the purpose of a setting is to "show off" a gem. If jewel-making stopped there, it would leave little enough excuse for this article in THE HOUSE BEAUTIFUL. |

|

|

|

It was once my privilege to penetrate to the recesses of the splendid mineralogical collection of Harvard University; to unlock drawer after drawer of minerals and see all the colors imaginable coming to life as the sunlight entered. The memory of that experience came back as I examined the jewels on Mrs. Shaw's table. There, on the one hand, had been the raw material, specimens assembled and labeled for the increase of human knowledge about the universe we live in; and here, on the other, was the finished product, gems and metals cunningly wrought into objects of art. A distinguished mineralogist has defined crystals as the "perfect individuals of the mineral kingdom"; and it simply carries the nature of the material to its logical conclusion when a jewel-maker seeks for like individuality in the jewels that give them an enduring setting. By this road jewel-making climbs beyond mere personal adornment and becomes a dignified art; and the possession of a fine jewel may become an indication of cultivated taste rather than of capability for lavish expenditure. Lavish expenditure, as often enough happens in matters of cultivated taste, may still be present; but it assumes a subordinate and more modest aspect.

Mrs. Shaw's workshop is a small room in the ell of the colonial house, with small windows that frame the external world like a row of landscapes, and a bench littered with the tools that constitute the goldsmith's torture chamber for the compulsion of metal into good ornamental behavior. I am tempted to call it a Reformatory for Delinquent Jewels; jewels, owing to an unfortunate early environment, that commit sins against taste. The reformation is remarkably thorough. A diamond ring, for example, in a conventional setting, is laid aside by an owner who has finally recognized that it is ugly and uninteresting; and then some day taken out of hiding, sent to Mrs. Shaw for treatment, and comes back home a ring that any finger may well be proud of. But a more vivid, even more spectacular, illustration was the transformation, some time ago, of two handfuls of diamonds in miscellaneous settings into a single necklace. The hands, by the way, were those of Miss Julia Marlowe. Here again description merely itemizes: so many diamond-dotted chains. of gold to encircle a neck; two rather massive designs in gold and diamonds, the precious metal in two colors and the diamonds, so to speak, woven into the texture of the filagree setting; and so many more chains of gold, scattered along their length with brilliants, reaching to the wearer's waist.

Such unique work explains why the craftswoman is a medalist of the Boston Society of Arts and Crafts; and why the Boston Museum of Fine Arts includes three specimens of Mrs. Shaw's work in its permanent exhibition of beautiful jewelry. For the older jewelry in that exhibition is not "immortal," to the extent of being still preserved and admired, because of any remarkable value in the gems used by the jewel-makers, "the old Italian masters," in some cases, of the New York art dealer, but lives by virtue of what they did with their material; and so expresses to a later century the dignity of art which Mrs. Shaw imparts to her work when she creates a jewel in the hope that its workmanship will enable it long to survive the period in which she created it. |

|

Naturally, an observer of these results wonders how they are accomplished. The stone itself, says the jewel-maker, suggests the setting: you study the gems, arrange and rearrange them, note the play of colors as they affect each other. Sooner or later an effective juxtaposition suggests itself; the design of the jewel begins to be tangible. The setting; mark you, is not to display the gem: it is not a shop window. Rather it must in the end combine almost spontaneously with your bits of crystallized color; and you will not ornament the metal for the mere sake of the decoration, but in order that the gem shall "melt into" it. In short, the color and decoration of the setting shall combine with the colors and structure of the gems to make a jewel in which a second glance, or even a reasonably close examination, is needed to discover just where the gem ends and the setting begins. And behind each step is the fundamental realization that nature has epitomized much of her beauty in the gem minerals, and that to combine them into jewels the jewel-maker can do no better than go to nature for helpful hints.

And so, meditating jewelry, I sprint along the railway track through woods deepening with night an undignified figure hunted by the thought that the last train till to-morrow may pass me before I get to the station. And it seems to me that Mrs. Shaw raises jewelry to a higher plane than most of us regard it, in that she seeks to create permanent worth where we have been wont to see ephemeral ornament. It has been stated, on good authority in such matters, that "a fashionable woman's list of artificers must now include a bijoutiere whom she consults regularly in regard to jewelry that will lend her distinction": it has even been said that Mrs. Josephine Hartwell Shaw is a bijoutiere. But for my own part I prefer to regard her as an honest craftswoman in the craft of making original and beautiful objects of art out of a few specimens of mineralogy. Leave "milady" her "bijoutiere," deciding for her whether she is tall enough to wear the "intricate, Oriental things" or " delicately fashioned " enough for the "fragile, tranquil ones," or "massive" enough I wonder what jewelry would be most becoming to an elephant for something else. And leave Mrs. Shaw, down there in the country, making jewels with the primary ambition to create something that will still be preserved for its own worth long after the most "massive" and the most "delicately fashioned" of her contemporaries shall be crumbled to dust together. |

|

|

|

|

|

|