Home Main Reference Page Main Index

THE KEYSTONE -- One of the leading jewelry publications, THE KEYSTONE, published an article in its November, 1910 issue detailing the Arts & Crafts jewelry of Josephine Hartwell Shaw (listed in the article also as Josephine "Huntley" Shaw), Margaret Rogers, and two lesser-known figures, Alessandro Colarossi and Lacey Twyman Rockwell. Accompanying the article are numerous examples of their work.

|

Technical Excellence as Represented by Some American Art Metalsmiths By IRENE SARGENT Five years since THE KEYSTONE printed the first article of a series dealing with the jewelers and the art metal-workers of the United States. This series was continued without interruption through more than eighteen issues of the magazine, each of which contained a number of representative illustrations upon the subject just named. From these illustrations and after the lapse of a half decade it is now easy to judge of the trend, during this period, of the art-craft here involved, as well as to foresee the direction which this craft will follow in the near future. It is plain that it has responded to a progressive demand for technical excellence.

Both the demand and the generous response which has been made to it are encouraging signs of the present day. They indicate a great expenditure of thought and resource on the part of the workers, as well as a distinct advance effected in the education of the public taste. They show that, in spite of the pessimism displayed by certain art critics, commercialism is subordinate to the respect for beauty in the minds, of both those who produce and those who purchase.

The early days of the Arts and Crafts Revival were characterized by a revolt against the systems of design which immediately preceded that movement. For the revival was at first, if the small may be compared with the great, a subversive, destructive, somewhat negative force in the sphere of art and industry, like the French Revolution in the world of politics and economics. In the temporary chaos so occasioned, extravagances naturally arose; these taking form in the works of the extremists in the Art Nouveau whose madness quickly spent itself, leaving "not a wrack behind." |

|

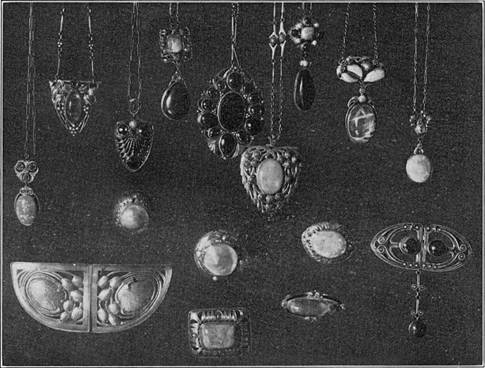

MRS. JOSEPHINE HUNTLEY SHAW

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

10 11 12 14 16 13 15 |

|

No. 1 -- Gold pendant with opal drop; the trefoil head is set with a sapphire and olivines. No. 2 -- Silver pendant, set with amethyst. No. 3 -- Gold pendant, set with garnets and a baroque pearl. No. 4 -- Gold pendant with chrysoprase drop; the upper figure has an opal in the center and in the border small sapphires, olivines and tourmalines. No. 5 -- Silver pendant with a carnelian as a central stone, the other gems in the border being Mexican opals and yellow -- green sapphires No. 6 -- Silver pendant, representing a cedar branch with berries, set with white carnelian and Russian lapis lazuli. No. 7 -- Gold pendant with apricot -- colored carnelian drop; the top is set with the same stone and baroque pearls. No. 8 -- Silver pendant, set with rose quartz and baroque pearls. No. 9 -- Gold pendant with opal drop; the top is set with sapphires, rubies and olivines. No. 10 -- Silver buckle in repoussé work. No. 11 -- Gold brooch, set with blister pearl, sapphires and olivines. No. 12 -- Silver brooch in motif representing the "Swirl of Water," set with blister and baroque pearls. No. 13 -- Silver brooch, set with sapphires and agate. No. 14 -- Gold brooch, set with opal and sapphires. No. 15 -- Copper and gold brooch, set with clatholite. No. 16 -- Silver cloak clasp set with Mexican opal. |

|

Then began a reaction during which a sane and successful effort was made to justify a new system of design based upon the study of the principles and proportions of Nature, but, at the same time, recognizing that the function of art is always to represent and never to imitate. By this very recognition the new system placed itself among the epoch-making phases recorded in the history of the minor arts, and, as a consequence of the truths thus discovered, we find that plant-analysis, as to both structure and distribution of color, occupies an important place in the courses offered by the best schools of decorative and applied art existing in Europe and America.

But it must be remembered that the consideration of design formed but one element -- and that one not the most important -- of the Arts and Crafts Revival; since inherent to it or, rather, constituting its very essence, was the demand for technical excellence which was supported as a sine qua non by the leaders of the movement and denied only by such as might be styled free lances: that is to say, individuals who, unwilling to purchase solid attainments at the price of hard work and infinite pains, yet hoped to gain prominence by eccentricity and pretense.

This demand for technical excellence was, in truth, a revival in the best sense of that term. It directed attention to a long past time, when the workshop occupied a place beside the school; when skilled craftsmen taught by the work of their hands that the right use of materials leads to the best, the most accurate expression in form and structure; when the designer and the executant were united in one man who so thoroughly knew his medium that he never misjudged its properties. |

|

It was the insistent desire to possess such technical excellence, such absolute integrity of expression, that sent William Morris, in the dead of night, to work at the bench and the loom; and his example of self-sacrificing diligence must be followed by every apprentice who would become a master-craftsman. The would-be artist potter must feel by actual contact that clay is plastic, just as the worker in precious metals, if he would assure success, must learn, not from a book, but by personal experiment, that gold and silver are malleable and ductile.

Furthermore, it is not solely the workers who are now convinced of these truths. The movement has, in all countries, extended to the aesthetic and the purchasing public: offering another of those frequent instances of popular education effected by a restricted number of professionals; perhaps the most noteworthy of such instances having occurred in the art-history of Holland, when, in the short space of eighty years, the moralizing and storytelling picture was completely superseded and set aside by the truly "pictorial picture" built up of color-values and of light and shade, and therefore making its appeal to the eye alone, while remaining in its proper sphere as an agent of sensuous pleasure.

With the same end in view great ceramists, like Taxile Doat of Sèvres, and others representing Denmark, Sweden, and the United States, have put forth their most recent efforts to obtain wares made interesting and beautiful by the technical qualities belonging exclusively to fictile products, such as texture, crystallizations, cloudings and glazings, rather than to adorn their pieces with miniature bas-reliefs and pictures -- those tours de force executed by the famous potters of a generation ago. |

|

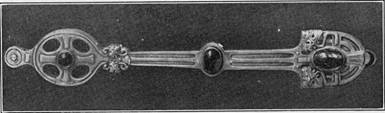

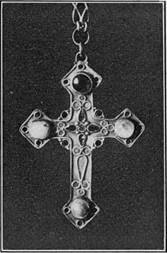

MR. ALESSANDRO COLAROSSI Lorgnon: Silver, set with amethysts en cabochon |

|

Responsive to the same demands for technical attainments, necessary in this age of extreme, if not always bitter, competition, those who are apparently the wisest of public educators advocate manual training for the masses and have succeeded in making it the principal branch of instruction in certain government schools, as at Zurich, Switzerland, or in combining it with theoretical studies bearing on the arts and crafts, as in Paris, Vienna, and Glasgow; while in the United States the action is as widely extended as the country itself: manual training having been established not only in the high, but also in the primary, schools of New York, Chicago and Philadelphia -- in the latter city the most active leaders of the movement being women, some of whom have contributed from scanty salaries means with which to further this admirable enterprise. Doubtless, also, an additional spur has been given to the impulse toward manual training in our country by the advances, alarming to us, recently reported as having been made by our industrial competitor, Germany, who hopes shortly to overcome our last few remaining advantages. A further factor in our awakening -- and the newest one of all -- is, perhaps, the timely economic instruction now offered by the statesmen who uphold the doctrine of "conservation;" since the thoughtful reader of their discourses cannot but deduce therefrom that loss of natural resources may be, in some measure, compensated by manual skill, and that the agricultural problem confronting us is not how many laborers till the Farm, but how much and what quality of products may be obtained from it.

* * * * *

The preceding considerations, made far afield from the art of the goldsmith, have yet the closest relations with it, and they have been stated purposely to emphasize, explain, and correlate with the active concerns of the world at large the labors of those enthusiasts for technical excellence whose productions are here illustrated. |

|

A rapid glance at the originals of these illustrations would convince the examiner of the intelligent means taken by the makers of the objects to secure the results which concur to form the goldsmith's ideal: that is, first, a spirited outline, dependent quite as much upon technique, as upon pure design, and lacking which the work fails utterly; second, a sureness of touch which makes every stroke complete in itself and of telling effect, like a well-constructed sentence; third, as a consequence of the latter excellence, a love of surface-quality revived from the days of the mediaeval guilds. In fact, the old and new are here blended in so convincing a manner that one may easily seize the principles of the goldsmith's art which were fixed, practically as we now know them, in the days of King Agamemnon. Here are the various patterns of coiled and twisted wire, the small chains used to connect the units of design, the minute balls and the granulations, only slightly modified from the use made of these devices by the early Greeks. Here, too, is the admirable, varied service of semi-precious stones, chosen for their beautiful color-effects and mounted in sprays of foliage, according to methods employed centuries before the affair of Queen Marie Antoinette's necklace, which marks the time when the diamond sprang suddenly into the highest favor, and goldsmiths began to diminish the beauty and importance of the mounting, in order to concentrate attention upon the jewel: thus pointing the direction which their successors gradually have followed, until to-day large brilliants are made to disguise their settings and connections as far as may be done, which often, when the stones are seen at even a short distance, is carried to the point of almost complete disappearance. But yet, in spite of these cunning devices of magical effects, the modest stones representing the resources of the Etruscan jeweler, added to certain similar ones made popular by the Italian navigators of the Renaissance period, and a few others of very modern use, offer most alluring charms, when they pass into the hands of craftsmen rich in skill, sympathy, and temperament, such as those who here receive mention. These persons are, with one exception, of American birth and training, although they have all enjoyed the advantage of extensive research in European capitals. The foreigner among them is Mr. Alessandro Colarossi, whose family name is everywhere known from its connection with the Parisian academy or atelier of painting in which hundreds of American students have worked under the criticism of many of the best artists of France. |

|

MR. ALESSANDRO COLAROSSI Casket and large spoon in silver, with circular bowl and pierced handle |

|

Mr. Colarossi, although of Italian blood and appearance, was born in London and has studied exclusively with English masters who seem to have subdued and swept away the more superficial of his racial qualities, or, it were better to say, those qualities which the Anglo-Saxon critic first observes as being opposite to his own; that is, devotion to fixed styles; a somewhat servile imitation of the classic; a love of excessive ornament. Yet the deeper part of this craftsman's nature as a Latin cannot be changed or moved. It asserts itself in his genius for structure. This quality, the most prominent of all those which distinguish the classic peoples, is first shown in full brilliancy in the Parthenon. It recurs in a new form, but essentially the same, in all that the Romans effected in political organization, lost for a time among the European nations of barbarian origin, it reappears anew in the arts of the Renaissance; while a strong proof of its intensely vital persistence is shown in the French architecture of our own day. Men are confident of self-mastery and believe that they can direct their own course of existence and expression. But they create and build only to reveal themselves completely, as exponents of their special race and in their own bare individuality. What they form out of material substance is truer and more eloquent than their speech, for they can teach their tongues to disguise their thoughts, while their hands remain the faithful servants of their brains and spirits.

Typical Specimens

For support of this theory we have but to criticize the concrete examples offered in Mr. Colarossi's work. In the lorgnon we find the observance of proportion and principality, the distinctness of outline, the symmetry and balance which characterize the best works of classicism from the great temple to the small vase. The clear mouldings would do honor to an Athenian artist of the best period, as would also the simplicity and sparseness of the ornament, which is so used as to represent natural growth. Indeed, the most obvious judgment to be passed upon this really important work is that it is pure and strong after the manner of a Greek nude. |

|

But the chastity of the piece entails no coldness. Life and warmth are imparted by large amethysts en cabochon, which divide the space rhythmically, and whose water-clearness seems to be the concentrated exuberance and the climax of the luster of the metal.

The casket, which is also the work of Mr. Colarossi, has the same structural qualities as the lorgnon. Its extreme simplicity of plan again suggests the classic; its profile satisfies the eye; its strengthened base-line and deeply-shadowed moulding announce the architect; while the craftsman who appreciates a valuable substance is shown in the spoon lying beside the casket, since we find here no thin plate-like treatment, which is proper only to the baser metals. Instead, the thickened, rounded edges of the stem, the pleasing degree of concavity given to the bowl supply the place of ornament, except where a spot of richness, needed to emphasize the composition, occurs in a pierced floral design set at the expansion of the handle. These three pieces, each remarkable of its kind, would show, even if it were not an acknowledged fact, that Mr. Colarossi is a deliberate, rather than a prolific, producer. Yet his reputation has spread East and West in the United States, although it centers in the Arts and Crafts Guild of Philadelphia, one of the studios of which he at present occupies.

An Accomplished Metal-worker

Another metal-worker and jeweler represented in our illustrations is Mrs. Josephine Hartwell Shaw of Brookline, Massachusetts, who received her professional education at the Normal Art School of her own State and at the Pratt Institute of Brooklyn, New York; afterward becoming assistant supervisor of drawing in the public schools of Providence, Rhode Island, and later an instructor in the same branch at the noted William Penn Charter School in Philadelphia: a position which is one of distinct honor, since this institution, which offers college preparatory courses for boys, has never lowered the ideals fixed two centuries ago by its great founder. |

|

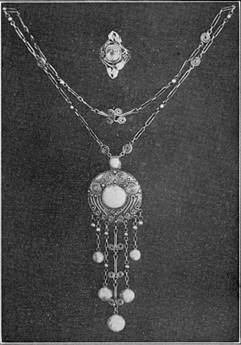

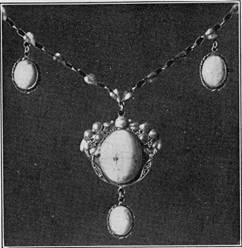

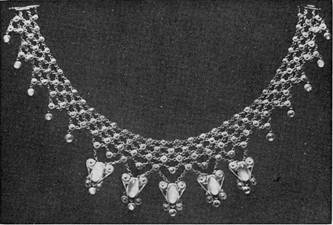

JOSEPHINE HARTWELL SHAW Silver necklace, set with turquoise |

|

Mrs. Shaw, as will be seen by reference to our illustrations, possesses much technical excellence. Her outlines are firm, the stroke of her tool effective and finished, her appreciation of the precious metals sound and sympathetic. We find everywhere announced that her medium is malleable and ductile. We have evidences of versatility in her pleasing variations of the goldsmith's resources in design: many types of chains, prominence of the ball-motif, all edges accented by fine mouldings or by twisted wire. Added to such technical excellences, which are the result of good training, diligence and general intelligence, there are indefinable, but strong, evidences in her work of a sentiment and vocation for the art of the goldsmith. These qualities, also, are apparent in the reproductions, since they reside partially in the design.

But what cannot lie told, except by the objects themselves, is the pre-Raphaelite charm of color produced by the gems and stones employed; most of the latter being of the semi-precious standard. In making these combinations Mrs. Shaw appears to aim at complex reflections, quite after the manner of a painter of still-life; as opals, rubies, sapphires, and olivines sometimes enter into a single piece, which, if correctly used, would produce an admirable focal point upon the costume of its wearer.

In looking at the more finely wrought of these objects, one recalls the portraits painted on wooden panels by the old Lombard masters, like De Predis and Luini, in which the sleeves are looped with curious jewels and pendants hang over the brow or from the neck chains of the subject. But doubtless it is the hand-wrought quality of Mrs. Shaw's modern work which induces these thoughts, quite as much as the forms or the gems which she employs. |

|

Miss MARGARET ROGERS Necklace, fine gold of pale green tint, set with smithsonite and pink pearl |

|

MISS MARGARET ROGERS Silver pendant and chain, set with turquoise and ornamented with enamel |

|

MISS MARGARET ROGERS Brooch in fine gold, set with green tourmalines and a pink pearl |

|

MISS MARGARET ROGERS Brooch in fine gold of very pale tint, set with rose quartz and chrysolites |

|

MISS MARGARET ROGERS Gold pendant and chain, tinted green and set with carnelian |

|

MISS MARGARET ROGERS Pendant and chain in fine gold, set with topaz and moonstones |

|

MISS MARGARET ROGERS Necklace, set with moonstones, green tourmalines and green and purple translucent enamel |

|

MISS MARGARET ROGERS Necklace, silver and gold, green enamel, topaz and moonstones |

|

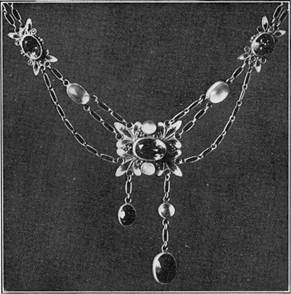

MISS MARGARET ROGERS Silver necklace, set with amethysts, green tourmalines and pearls |

|

Other of her pieces show the study of Anglo-Saxon and of other early mediaeval methods and styles. Such, for example, the necklace set with turquoise, which is a well spaced rhythmical design, containing many of the essentials of artistic composition -- notably symmetry, stability, and the repose resulting from the two former qualities. Finally, a slight French influence of to-day, derived from Lalique and Fenillátre, appears in such examples as the branch of cedar with berries and the silver buckles. But this influence is plainly not an imitation. It is simply a recognition on the part of Mrs. Shaw of good design and sound technique, as determined by the limitations of the goldsmith's art.

Another Lady Artist

In a third group of our illustrations are presented examples from the studio of Miss Margaret Rogers, of Boston. These to a careful observer recall the saying of an English critic that "ornament is the exuberance of good workmanship;" for it would be difficult here to separate the technique from the design. Unlike Mr. Colarossi, whose tendencies are toward the classic, and Mrs. Shaw, in whose sympathetic work we catch glimpses of a long succession of old artists and craftsmen, Miss Rogers seems merely to gather the sum of the legacies left by the masters, which she uses as a working capital of methods in a simple, logical manner.

This lady, born and educated in Boston, received a general art training, during the course of which she was strongly attracted to open-air sketching. But possessing decided mechanical ability, she later chose to devote herself to work in the precious metals, enameling, and jewel-setting, all of which branches she pursued under excellent technicians. Then, having gained through actual experience the appreciation with which to profit by foreign travel, she broadened her knowledge by museum study in Paris, London, Florence and Naples, as well as by acquainting herself with the work of all great contemporary European goldsmiths. |

|

Miss Rogers acknowledges that she works preferably in colored stones associated with enamels, and the results which she thus obtains justify her choice of mediums. Her use of translucent pastes show the feeling of an artist who understands that she is dealing with a precious jewel-like material, which must beautify small spots. Accordingly, we find accents of this substance in purple and green combined with the elusive, veiled luminosity of moonstones and green tourmalines in a necklace, designed upon a floral motif, which is artistically obscure and conventional, but evidently studied from a water-lily through a long series of notes.

In another example, also a necklace, the color-scheme is afforded by yellow topazes and green enamel to which contributory "values" are added by moonstones and the soft surface treatment of gold and silver. The design of this piece also calls for a word of comment, since the structural devices are made to furnish the detailed ornament, as may be seen by examining the rings which hold the chains so securely in place.

Color Pre-eminent

But in this, as in all the other examples here presented of Miss Rogers's work, color is the principal element, and we may imagine her at work, placing her "spots," and then providing that good technique realize her first conception. It is further to be observed that these schemes of color run the fascinating gamut of the pastel shades; for besides the greens and the yellows already noted, there are combinations of rose quartz and chrysolite, pink tourmalines and olivines, green tourmalines and pink pearls and of these latter with pale green gold.

Still, in spite of this predominance of color, it must be urged once again that Miss Rogers, in such examples as her silver and turquoise necklace and her pendants set with smithsonite, and carnelian, proves that "ornament is the exuberance of good workmanship." |

|

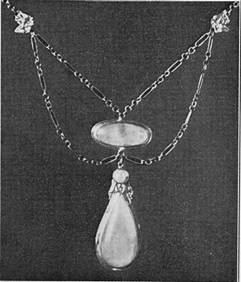

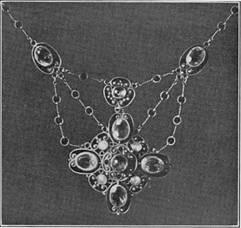

MRS. LUCY TWYMAN ROCKWELL Necklace: Silver and gold, set with oriental moonstones |

|

MRS. LUCY TWYMAN ROCKWELL Collar in pale matt gold, set with deep yellow table-cut topazes |

|

MRS. LUCY TWYMAN ROCKWELL Necklace in pale matt gold, set with honey-colored topaz |

|

A Philadelphia Artist

The last of the four artist-goldsmiths whose productions Artist we have chosen to review is Mrs. Lacey Twyman Rockwell, of Philadelphia, a woman of temperament, of actual accomplishments and of yet greater possibilities. The father of Mrs. Rockwell, Mr. Joseph Twyman, who was a mural painter and interior decorator of reputation, worked in Chicago in the days of that city's crudeness, and there accomplished results similar in kind, if not in extent, to those effected by William Morris, when he delivered Victorian London from the scourge of the haircloth sofa and the antimacassar red with the blood of murdered time.

Inheriting much of the ability of her parent and principally instructed by him, Mrs. Rockwell has also followed courses of study in several schools of art, while in metal work she is the pupil of Mr. Colarossi. She has further observed and studied much abroad by visiting museums and workshops, especially in England, which was the native country of her father, and whose modern art she greatly admires.

As a metal-worker she has already attained maturity and struck a distinctive, personal note. Her designs are coherent and easily read, her treatment of color subtle, her handling experienced and assured.

The quality of coherence and clearness is as strong in the most complicated, as in the simplest of her designs. But it is well to begin with an example of the latter class. This is a necklace, a beautiful composition of roses and foliage, offering in response to a first glance, the essential character of the plant. Yet the plant is stiffened and conventionalized, that it may yield to the properties of metal and, therefore, to the demands of art. Such, indeed, was the treatment of the English Gothic carvers who adapted the flora of the region to the medium of stone and to the architectural spaces to be filled. The rose necklace is furthermore distinguished by great delicacy of design, workmanship, and color; the little "repeats" of the motif being especially pleasing, and the dull, pale gold of the setting enhancing the transparency of the deep yellow topaz. |

|

For the subtle treatment of color the ring and moonstone necklace serve as examples. The ring is a free adaptation of a class of designs belonging to the late mediaeval and Renaissance periods, and showing sprays of foliage in which glowing jewels are couched. Mrs. Rockwell has chosen for her stones Maine tourmalines in honey-yellow and spring green, with which and a transitional note of fine, matt gold she has produced a most refined and beautiful effect.

A result much more difficult to describe Mrs. Rockwell has obtained in a necklace intended to be worn with a bridal gown. In this a closely-woven, armor-like chain is set with small silver balls, each bearing a minute point of gold at the summit, while the bluish and yellow opaque tones of the metal contrast with the same colors, which glint through the bodies of large pendant moonstones. It is quite needless to make allusion to the design of this ornament as presenting in the woven chain a similarity with old Spanish work, or as offering in the pendants a disguised scarab-and-lotus motif, since the evanescent effect of the whole purposely dissolves the composition.

The last and most important of these examples is wrought with the patience and love of a craftsman of the old-time guilds. It is a collar formed of a series of units composed on a rose motif, again Gothic in its subtlety of adaptation and in its varied detail; no two of the bosses being absolutely similar. Its color scheme is an assemblage of yellow tones made by dull gold and table-cut topazes, and among which brown and purple pearls appear like the shadows of the yellows; the whole suggesting the treatment of the brocade known as cloth of gold, which occurs in the portraits of the Venetian masters, Bellini and Paolo Veronese. It is remarkable that this jeweled collar in design, color and technique, while it bears not the slightest mark of imitation, should so consistently represent the period of the Emperor Charles Fifth, when the arts and crafts most flourished.

But may not technical excellences such as are presented by the experts of today, prepare a union of the new and the old which shall eclipse all that has gone before. |

|

Art Antiques and Their Prices

A leading authority in the world of art recently stated that there are two particular causes for regret in connection with the giving of inflated prices for art antiques. First, museums which are public institutions are unable to compete, and pieces which are valuable as objects of study pass into private collections where little more is seen of them. In addition to this, it is obvious that for a sum such as a wealthy man could give for one antique piece, a large number of modern or current pieces could be purchased which would offer encouragement for the art of our time, in regard to which laymen have a responsibility no less than artists. Where, however, an antique has no particular virtue save its rarity or antiquity or the price it will fetch in the market, one cannot help regretting that the purchase money has not gone to foster present-day art. To the argument against giving large sums for antique pieces, the obvious reply is that no modern counterpart is produced equal in merit to the old. This is to some extent true, but the times have greatly changed. |