Home Online References Main Index

History of American Silver -- In a 1916 issue of The American Magazine of Art (which had just changed its name from Art and Progress), the noted Henry P. Macomber, Secretary of the Society of Arts and Crafts, Boston, presented an excellent history of silver-making in the United States.

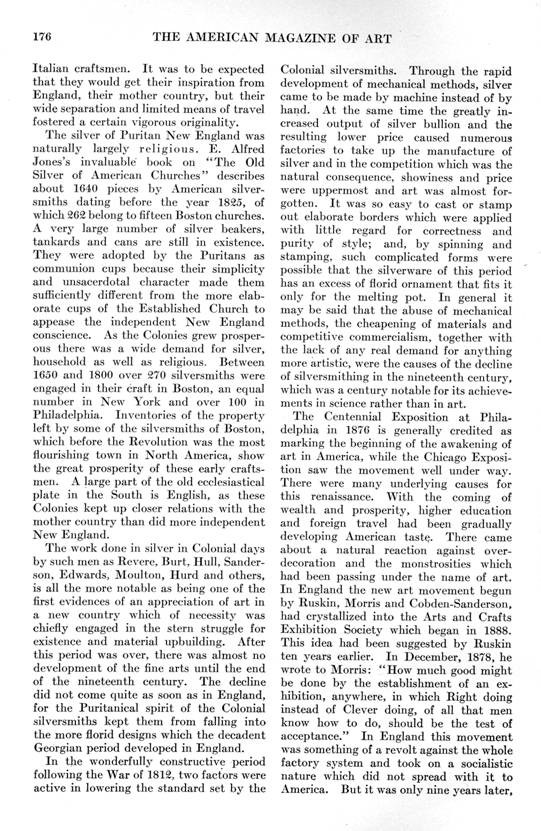

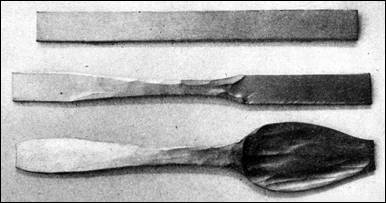

Initial steps of handmade spoon manufacture

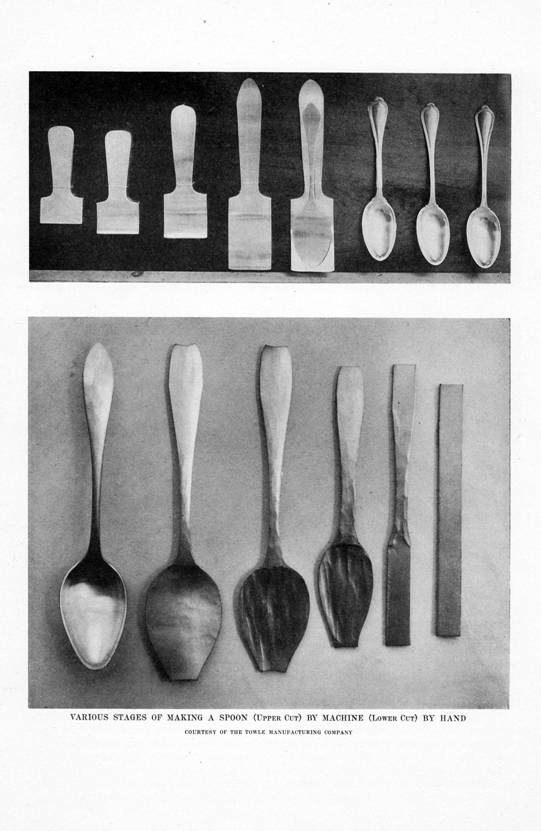

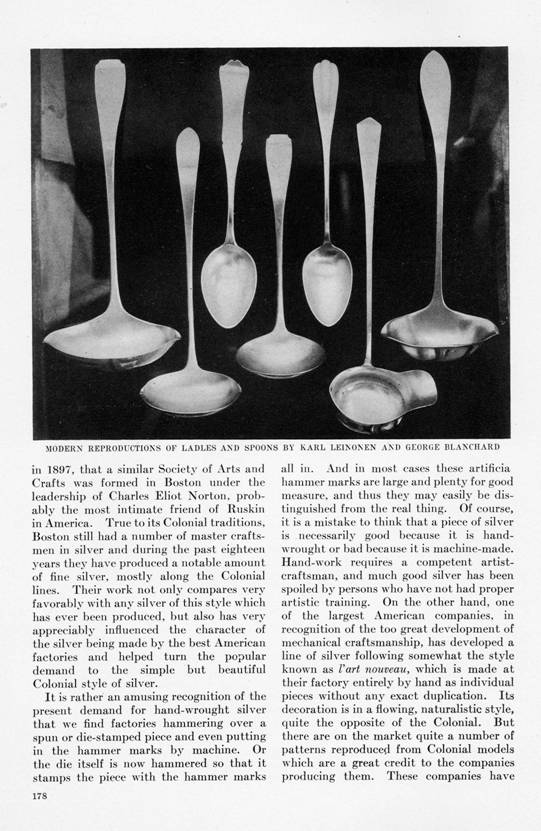

Among the Arts & Crafts tenets were an appreciation for simplicity of form and line, a rejection of fussy, over-ornamented detail, and an emphasis on art that was useful. According to Macomber, these views were uniquely American and dated back to colonial days:

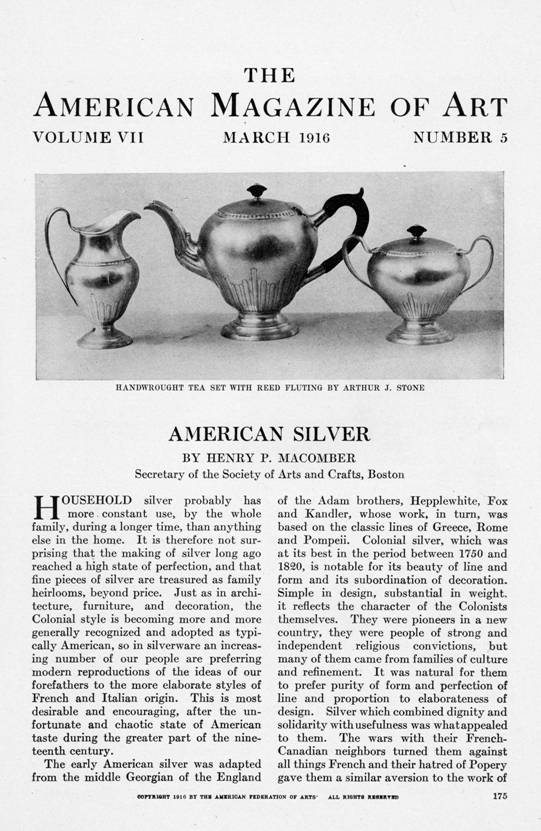

"Colonial silver, which was at its best in the period between 1750 and 1820, is notable for its beauty of line and form and its subordination of decoration. Simple in design, substantial in weight, it reflects the character of the Colonists themselves. They were pioneers in a new country, they were people of strong and independent religious convictions, but many of them came from families of culture and refinement. It was natural for them to prefer purity of form and perfection of line and proportion to elaborateness of design. Silver which combined dignity and solidarity with usefulness was what appealed to them. The wars with their French-Canadian neighbors turned them against all things French and their hatred of Popery gave them a similar aversion to the work of Italian craftsmen. It was to be expected that they would get their inspiration from England, their mother country, but their wide separation and limited means of travel fostered a certain vigorous originality."

But, as he observed, the dawn of the machine age in the early-1800s contributed to a degradation of silver quality:

Through the rapid development of mechanical methods, silver came to be made by machine instead of by hand. At the same time the greatly increased output of silver bullion and the resulting lower price caused numerous factories to take up the manufacture of silver and in the competition which was the natural consequence, showiness and price were uppermost and art was almost forgotten. It was so easy to cast or stamp out elaborate borders which were applied with little regard for correctness and purity of style; and, by spinning and stamping, such complicated forms were possible that the silverware of this period has an excess of florid ornament that fits it only for the melting pot. In general it may be said that the abuse of mechanical methods, the cheapening of materials and competitive commercialism, together with the lack of any real demand for anything more artistic, were the causes of the decline of silversmithing in the nineteenth century…"

Starting around the time of the Centennial Exposition at Philadelphia in 1876, America underwent a renaissance in decorative arts that eventually became the Arts & Crafts movement. Macomber explained why: "With the coming of wealth and prosperity, higher education and foreign travel had been gradually developing American taste. There came about a natural reaction against over-decoration and the monstrosities which had been passing under the name of art."

The full text of Macomber's piece, which ends with an interesting discussion of the merits of hand-work versus machine-made objects, is below.

|

|

|

|

|

|