Home Main Reference Page Main Index

▪ How Silver is Made ▪

-

PREPARING THE ALLOY FOR PLATED SILVER

Copper is replaced by an alloy called nickel silver in modern plated ware

In 1937, the Brooklyn Museum mounted a show called "Contemporary Industrial and Handwrought Silver" that included works by:

|

The Alvin Corporation Benduro, Inc. Charlotte David Bone The Brand Chatillon Corp. Edward F. Caldwell & Co. Cartier, Inc. Currier & Roby, Inc, Laurits Christian Eichner George E. Gebelein International Silver Co. Indian Arts & Crafts Board Christian A. Jakobb Georg Jensen Arthur Nevill Kirk |

Samuel Kirk & Son Thetis Lemmon Morris Levine Esther Lewittes E. Byrne Livingston Paul A. Lobel Erik Magnussen Peter Muller-Munk Otto Meissner Oneida Community Tommi Parzinger John P. Petterson Charles B. Price Francisco Rebajes |

Reed & Barton Rogers, Lunt & Bowlen Co. William Spratling Rena Rosenthal Harold Tishler Towle Manufacturing Co. Albert A. Verber Ilse Von Drage Alvin Von Hinzmann The Watson Company R. Wallace & Sons James T. Woolley |

The catalog contained numerous examples of handwrought and machine-made silver (although it neglected to showcase any works by Rebecca Cauman or the Kalo Shop's Clara B. Welles). In it were definitions of "hollow-ware" ("silver which encloses any amount of cubic space is called hollow-ware. In this classification fall bowls, vases, tea and coffee services, cups, etc. All are adaptations of the fundamental round bowl form") and flatware ("silver largely in one plane, which does not enclose any cubic space. It has come to mean knives, forks, spoons and serving pieces").

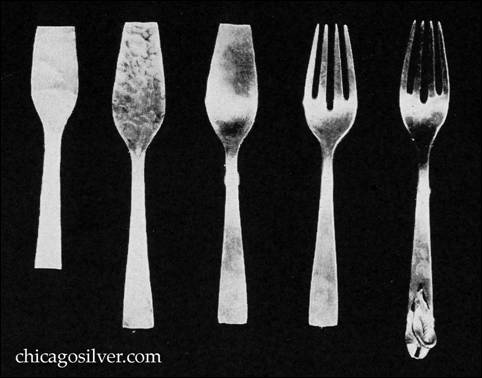

It also included step-by-step photos showing how machine-made flatware is fabricated, as well as the five steps Peer Smed used in making a handmade fork. It also covered the silver-plating process and chasing.

|

FOREWORD

The aim of this catalogue and of the 1937 Exhibition of Contemporary Industrial and Handwrought Silver is to present in brief present-day American silver production. As an introduction, 18th Century English and American Silver is included, which is largely the source of the forms and decoration used today. These few important pieces represent a high point in skilled craftsmanship.

The catalogue and the Exhibit are particularly concerned, however, with contemporary silver. In the largest gallery characteristic work of the outstanding sterling firms is shown in separate cases. Thus it is apparent which firms are conventional followers of tradition, and which radical, or which firms have a large element of skilled hand labor and which depend mostly on modern mechanical means for a large, rapid production. The firms are grouped along one side of the sterling gallery, while the individual silversmiths occupy the other. Here again, each designer is given a separate case, so that the personal styles which together make up the contemporary American production may be clearly evaluated. While the exhibition is almost entirely of American work, it includes some Danish and some Mexican silver, as these have had a strong influence on American silversmiths. Sterling jewelry is represented, as well as all the usual types of domestic silverware.

Next in the sequence of galleries is a small section of Old Sheffield Plate, made by the "fused," or "rolled" process of combining sheet copper and silver. Finally, there is a gallery of modern electroplated silver, including lighting fixtures, especially light ware for passenger airplanes and a variety of industrial applications of the modern plating process. There are demonstrations of the various techniques of hand and machine-made silver throughout the course of the Exhibit.

Our aim is to be as objective as possible. Handwrought and machine-made silver stand on their own merits. The difference between the surface of hand-hammered and spun or machine-stamped silver is pointed out. The subtle irregularity and dim polish of the first is contrasted with the mechanical evenness and brilliance of the other. Chased and engraved and pierced decoration done by hand or done by marvelously complex machinery is compared. However, the inter-relation of skilled manual work and the machine is stressed. The special qualities of each is stated, without crusading for a return of the handicrafts or for progress and the machine.

Similarly, we do not attempt to pass judgment on the esthetic values of the various types of silver represented. Examples of conventional adaptations of 18th Century period designs and of strictly contemporary work have been assembled and all are as fine representatives of their types as could be obtained. It is hoped that this juxtaposition will bring out clearly the qualities of silver. Everyone can then judge which type shows most clearly the malleability, the strength and the beauty of color and surface.

In the remaining space of this foreword, a few of the techniques of silver working will be briefly discussed. Hand and machine processes will be described with emphasis on their inter-relation. These few definitions are intended to indicate the complexities of working silver, and how these problems determine the final form. |

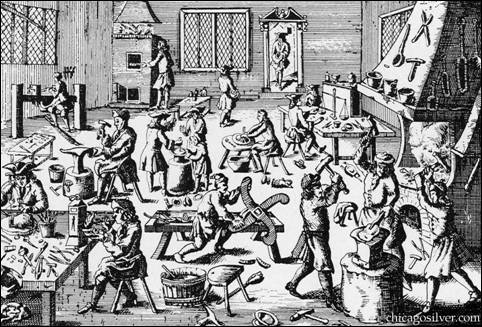

1707 engraving of a silversmith's workshop

|

All silver which encloses any amount of cubic space is called hollow-ware. In this classification fall bowls, vases, tea and coffee services, cups, etc. All are adaptations of the fundamental round bowl form.

Handwrought hollow-ware, made by 18th Century or present-day craftsman, is "raised" from a circular sheet of silver. The edge of the sheet is placed on a crimping-block, which has a depression in its center. The hammersmith strikes the sheet, forcing it down into the depression, until the entire edge has become fluted. With another type of hammer, the craftsman smoothes out the flutes and the sheet begins to assume a concave shape. Often a wooden form is placed in this hollow during the later stages. The crimping and hammering alternate until the desired form is realized. As hammering makes silver brittle, the piece is annealed or heated red hot, from time to time, to restore its tensile strength. Finally, the heavy hammer marks are effaced with a planishing hammer. Blows from this small-headed tool are laid side by side over the entire piece, giving a shining, slightly irregular surface. The unevenness refracts the light more brilliantly than the perfect surface of mechanically produced silver.

Various other parts, such as spouts, lids, handles, etc., maybe hammered into shape much as the body is and soldered into place. Often rims or bases are reinforced with one or more moldings. Silver wire is drawn through a series of tapered apertures, dies, in a draw-bench, until it takes on the desired size and shape. It is also soldered onto the parts of the object that receive most wear.

This whole process of "raising" hollow-ware from sheet metal requires extremely skilled labor. It is slow and heavy work, which inevitably limits production and makes the cost of the silver produced correspondingly high. The mechanical method which provides quantities of silver at lower prices is called spinning. A circular sheet of metal is fastened onto a revolving lathe, with a wooden form behind it called a chuck. The craftsman presses with a steel tool on the sheet as it spins around, forcing it to take the shape of the chuck. This requires great control and judgment on the part of the workman, as the amount of pressure he exerts determines the gradations of the final form. Sometimes concentric circles may be seen on the back of spun objects, made by the' craftsman's steel tools. The spinning process for an ordinary bowl takes about two minutes, and then the piece is polished with emery belts and sand buffers to a flawless surface. |

MAKING FLATWARE OR TABLE SILVER ON AN INDUSTRIAL SCALE

The craftsman first makes a precise model by band of each piece

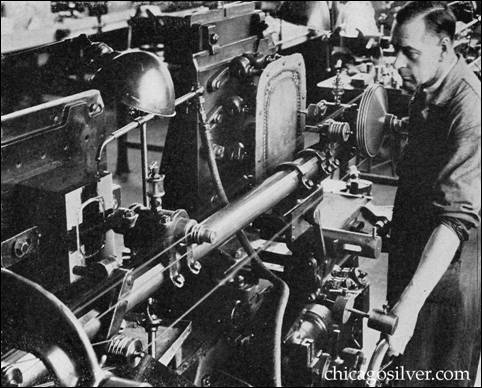

DIE-CUTTING MACHINE

This complex mechanism forms the mould or die with which

large numbers of pieces may be stamped

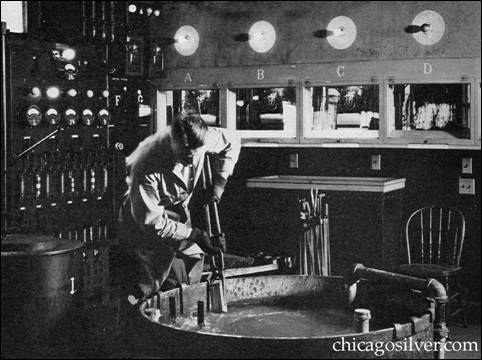

ANNEALING THE DIE

Silver becomes brittle from pressure and this heating process

restores its tensile strength

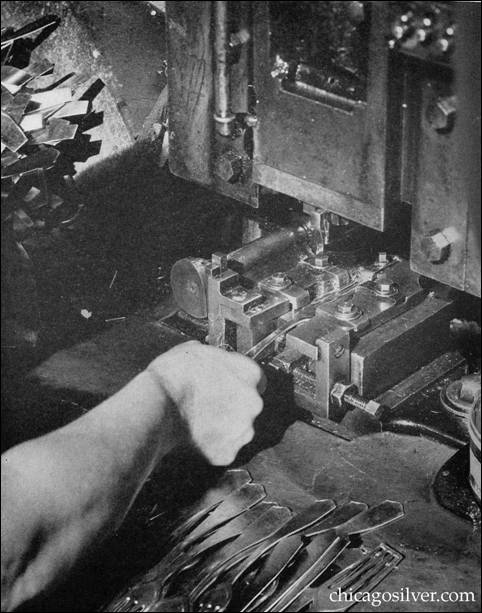

CUTTING ROUGH OUTLINES FROM SHEET SILVER

This machine cuts about twelve pieces a minute

CUTTING THE TINES IN FORKS

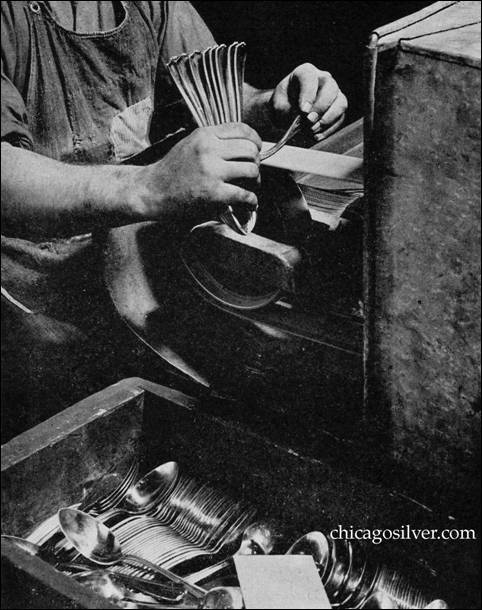

POLISHING THE BOWL OF SPOONS

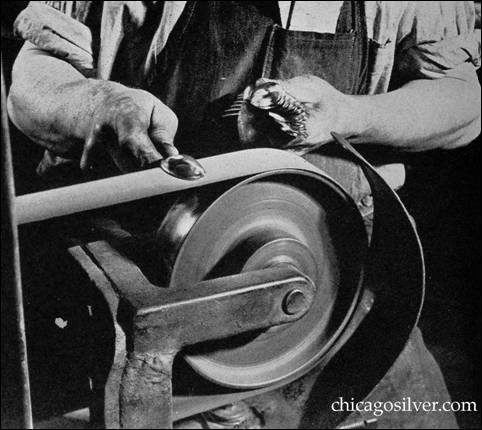

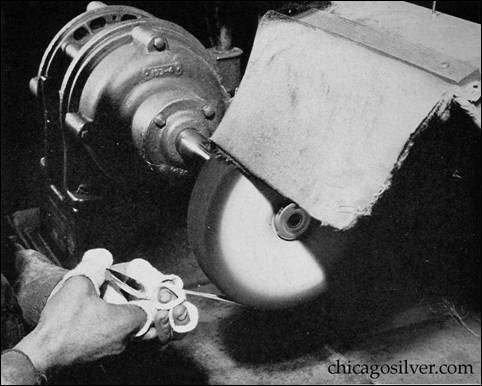

POLISHING

The flatware which has been stamped with the desired design on handle

and bowl is being polished on an emery belt

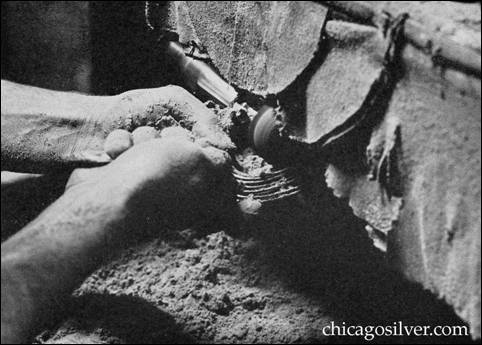

SAND BUFFING

POLISHING

There are at least six stages in polishing modern manufactured silver.

It is possible to obtain a perfectly even, brilliant surface by machine

that was unknown to old handmade silver

|

Flatware, as opposed to hollow-ware, means silver largely in one plane, which does not enclose any cubic space. It has come to mean knives, forks, spoons and serving pieces. When made by hand, each piece is cut out roughly, and directed by varied hammering into its final shape. Filing and polishing complete the tedious process.

The mechanical production, which makes it possible for almost all homes and hotels to have sterling or plated flatware is more complicated. Two dies or moulds are made for each spoon, knife or fork. These strike with tremendous force, and simultaneously, the rough form cut from sheet metal. They stamp the designs on both sides of the handles, and force the silver into a concave bowl, or cut the tines, as each kind of flatware requires. The dies are extremely expensive, often costing thousands of dollars. They are made from specially forged steel, cut by hand with the greatest precision. After they have stamped the flatware, it is polished with abrasives and emery belts and given the desired finish. |

FIVE STEPS IN THE HAND PRODUCTION OF FLATWARE

by Peer Smed

|

Old Sheffield Plate and Electroplated Silver

The "fused" or "rolled" plating process was discovered by Thomas Boulsover in 1743 in Sheffield, England. He found that sheets of copper and silver wired together and bathed with a fluxing solution, would fuse when heated. The resulting sheet could be worked like silver, although it was considerably cheaper to produce. There were always certain difficulties, however, as the outer sheet of silver in hollow-ware tended to stretch and "bleed" or reveal the copper foundation.

Electroplating, which began to replace the older process in the 1840's, coats evenly in a minimum of time, and requires very little silver. A piece of silver immersed in a special electrically charged solution, acts as an annode [sic], gives up its molecules which flock to the cathode, or object to be plated. By circulating the object slowly an even coat is assured. Nowadays nickel silver is usually used as the base metal, rather than copper. |

|

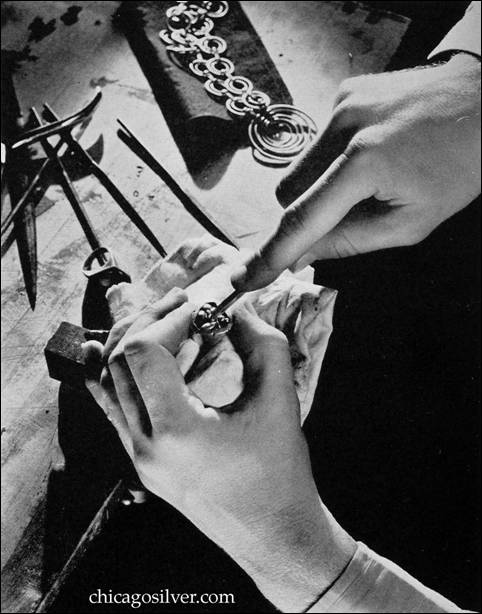

Modern silversmiths as well as Coney and Revere make cast ornaments in casting flasks. These consist of two wooden boxes filled with sand. A model of the object to be cast is pressed into each half, removed and the boxes bound together. Molten metal is poured into the resulting hollow impression and when it hardens the casting is taken out, filed and soldered into place. The modern industrial process is based on the same principle. However, the casting flasks are filled on endless belts and the slow human labor almost eliminated.

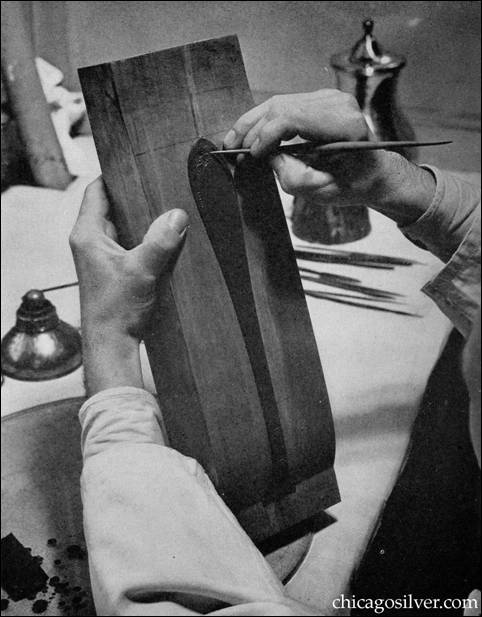

CHASING -- The craftsman indents the surface of the metal with a blunt-edged tool

Chasing and Engraving

In chasing, the silversmith fills his piece with pitch and indents the outer surface by pressure from a blunt-edged tool. On the other hand, in engraving, he actually cuts his design into the surface of the metal, which gives a brighter effect. Industrially, chased decoration is stamped from dies and often touched up by hand. Engraving may he done by special machines or by craftsmen retained by the company for its finest products. |